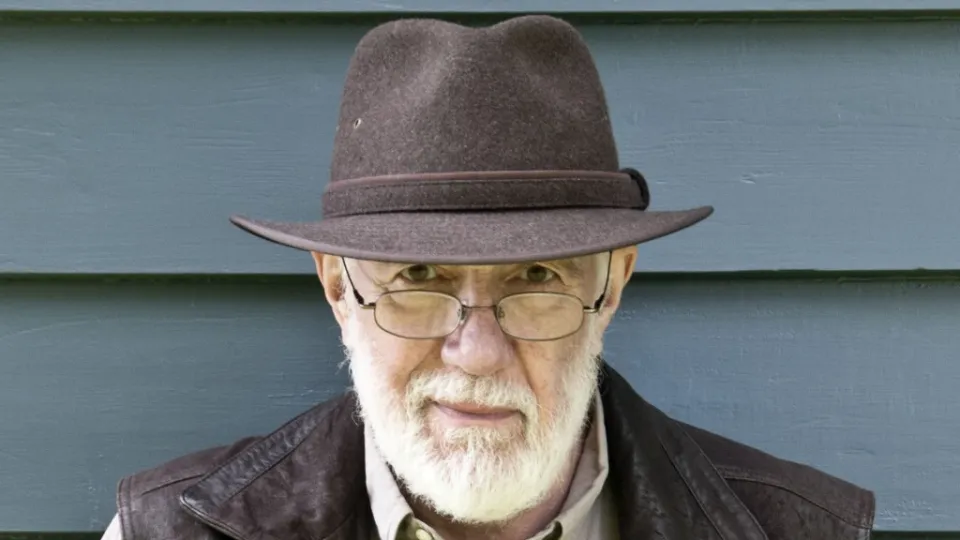

John Redfern (1939-2019)

John Redfern was the pioneering animator of watch and clock movements.

Not bad for someone who left school without any technical qualifications and who started using computers only in his 40s. What he did have from an early age was a passion for anything mechanical.

He started his career as an editor in the film industry, working on movies such as Spartacus. Only in his 30s did he become interested in clocks and started taking them to pieces to learn how they worked. Fascinated, he built up a business repairing and restoring them. He was skilled and meticulous and rapidly built up a clientele on both sides of the Atlantic.

In the 1980s he started to lecture at London’s Science Museum. Frustrated with the drawing tools then available, he took a course in computer graphics – he said that the day he discovered that he could draw a single tooth and then replicate it around a circle to create a cog wheel “changed my life!”. This was the era of Intel’s 386 chip, screen resolution was 640 x 480 and there were was just 256 colours – rudimentary by today’s standards.

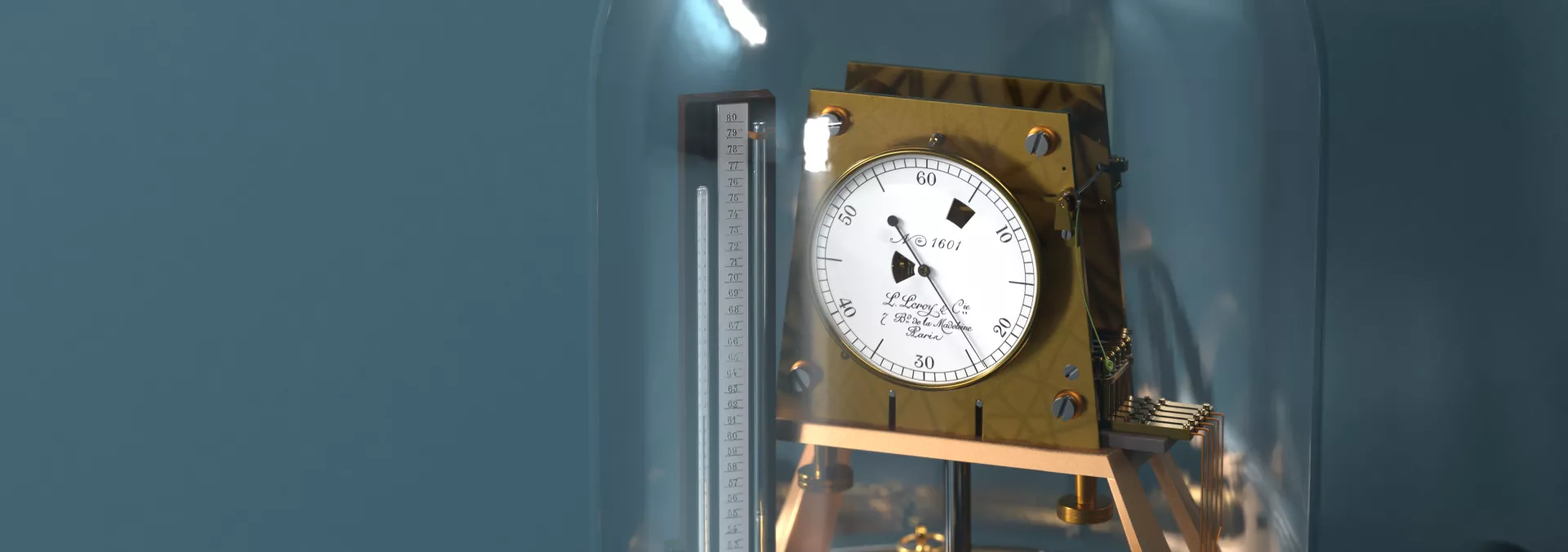

There’s a problem when it comes to understanding the workings of a timepiece – often the parts you need to examine are too small, too fast moving, or simply hidden. So you must take it apart to see how the various components interact. But it takes a lot of experience to understand a complex movement simply by looking at the parts.

When animation software appeared, Redfern’s key insight was that he could build a virtual clock and see into its heart while it was still working. You could slow it down, highlight key parts, remove things that hid or distracted, look from different vantage points and so really understand what was going on in a way never previously possible.

Redfern built a virtual working clock and ‘fly through’ as proof of concept, eventually being commissioned by Jonathan Betts, then of the Greenwich Maritime Museum, to make an animation of Harrison’s celebrated H1 which ran alongside the original for many years.

As software developed, and speed and resolution of the hardware increased, so he kept up with new techniques and capabilities, becoming a beta tester for Autocad. But still he wanted more. When the revolutionary RED digital cinema camera appeared, Redfern bought an early model with little idea of what it could do. As ever, he worked it out for himself, learning how to integrate video seamlessly with computer graphics. The results astonished him. Firstly, he found that the quality and accuracy were exceptional – he could now fill a movie screen with an area just a few millimetres wide. And with the addition of motion-control equipment the camera and the timepiece could both be precisely moved.

But the real breakthrough was that all three - the software, the camera, and the motion control equipment, could all talk to each other.

Setting the parameters in any one of these, they could be instantly communicated to the others, allowing the paths and timing set in the animation to be exactly replicated by the camera. Equally, the camera’s settings, such as lens type, exposure, perspective and depth of field, could be reflected in the animation.

This was what he had been chasing for over 20 years: the ability to combine high quality filming with cutting edge computer graphics.

Redfern was never interested in the technology for its own sake. He remained true to his love and understanding of film and of teaching. Everything he did focused on explaining complicated mechanisms and principles so that they could be understood by viewers of all ages and abilities, yet be enjoyed by the expert.

As his friend and colleague Will Andrewes observed, Redfern’s animations were done for the love of the object and the excitement of learning. Love and passion for the subject are really what set his work apart.

Martin Conradi